As an RPG GM I like to think of myself as a jack-of-all-trades rather than a one-trick-pony. Not that there’s anything wrong with only playing or running one system, if nothing else it allows for a great deal of system mastery that can be utilized to run great games, but for myself I like to experiment with a variety of games and systems.

One such game that I have been running, playing, and generally enjoying, is Apocalypse World. This game uses a system that many (if not most) traditional RPGers may find strange or difficult to grasp. As such, I would like to give you an introduction to the game from someone who enjoys it. This is more overview than review, but I do throw in reasons I like the system towards the end. I hope this gives you an idea of what Apocalypse World is, what it can do, and perhaps it will spark in you the desire to try the game out. I highly recommend it.

APOCALYPSE WORLD

Apocalypse World is a near-future post apocalypse game about the desperate struggle to survive in a strange and dangerous world.

Setting

Nobody remembers how or why. Maybe nobody ever knew. The oldest living survivors have childhood memories of it: cities burning, society in chaos then collapse, families set to panicked flight, the weird nights when the smoldering sky made midnight into a blood-colored half-day.

Now the world is not what it was. Look around you: evidently, certainly, not what it was. But also close your eyes, open your brain: something is wrong. At the limits of perception, something howling, ever-present, full of hate and terror. From this, the world’s psychic maelstrom, we none of us have shelter.

This is your introduction to the world of AW. What happened to make it this way? No-one knows. Perhaps you will define it as part of your game or perhaps it will stay unknown. Perhaps it is a central focus of your campaign or perhaps it matters not one bit. This is for the players to decide – how do you know what has been decided? Play to find out.

System

The game is set on a few simple principles. PCs have 6 stats that help define how well they can do certain things:

Cool: As in clear-thinking, calm, rational

Hard: As in hard-hearted, aggressive, violent

Hot: As in attractive, gracious, inspiring

Sharp: As in smart, perceptive, educated

Weird: As in uncanny, psychic, strange

Hx (History): As in shared history, how well one character knows another

These stats are given a value from -3 to +3, and they can change based on actions in the game. When one of them hits -4 or +4, it reverts to -1 or +1 (respectively) and the PC gets to advance (usually picking a new skill or move for the PC).

The PCs

Here is a list of the playsets (character types) that come with the main rule book:

Angel: Basic healers, post apocalypse doctors

BattleBabe: Main Strongarm, brute strength and charisma

Brainer: Weird psychics, strange mind-reading and mind-f*%$*ing characters

Chopper: Motorcycle gang leader, heavy duty security

Driver: Car and truck drivers, your post-apoc transport service

Gunlugger: Arms dealer, black market merchant

Hardholder: Landlords of the apocalypse, slumlord or savior

Hocus: Cult leader or religious prophet? you decide

Operator: Opportunistic popular jack-of-all-jobs, post apoc utilitarian?

Savvyhead: Stuff breaks, this guy can fix anything

Skinner: Artistic attention whore, charismatic bard

The main mechanic is very simple: When a PC does something they roll + a stat. The roll is always 2d6. If 2d6 + stat is less than 7, the roll is a miss. If the roll + stat is 7-9 that is a hit and the PC decides the outcome of the move based on a few seemingly limited choices. If the roll + stat = 10+ it is a very good success and the choices are different.

The things that PCs can do during the game are called moves and each PC has a set of basic moves that are available to everyone as well as special moves that only that PC type can use. Each type of PC also has a special sex move that (usually) provides some benefits to the PC when they have sex with a PC or NPC. Each game can only have 1 of a given type of PC so there will be no overlap of special moves or sex moves.

One of the most interesting aspects of this game is that it is highly scripted and upon reading sounds like a player’s options are very limited by the scripting. However, an amazing thing happens in-game and one finds that the restricted choices do not actually limit the game at all. This is because the game is built on the narrative and the outcome choices for moves are relatively vague and leave space for the narrative to take over.

Example of Scripting:

One basic move is called Going Aggro on someone. It means that the PC is using violence or the threat of violence to control someone else’ behavior, without (or before) fighting. On a roll+stat of 7-9 the target chooses 1 of the following outcomes:

a. Get the hell out of your way

b. Barricade themselves securely in

c. Give you something they think you want

d. Back off calmly, hands where you can see

e. Tell you what you want to know (or what you want to hear)

On a roll+stat of 10+ the target must choose 1 of:

a. Force your hand and suck it up

b. Cave and do what you want

Note that on a 7-9, the target can choose to force or cave as well as the initial 5 choices.

While these seem like heavily scripted responses that determine the outcome, they are actually rather vague if you think about it. The narrator gets to determine the true consequences, guided by the script. Let’s take Get the hell out of your way for instance. This could be interpreted and narrated in several different ways, from jumping out a window to get away from the Aggro PC to diving behind a desk, so frantically saying, “okay, okay, I am not going to do anything to get in your way” and moving quickly out of the way. The only thing the script really requires is that the target act fast and get out of the way. Acting fast is required because that is what differentiates that choice from Back off calmly hands where you can see them, but the target gets to choose exactly what is done. The narrative really determines how that actually plays out in-game.

In AW, the Game Master is called the Master of Ceremonies (MC). The game is meant to be a low prep game for the MC and the rulebook gives several hints and tips to make it that way. The MC has a different set of moves than the PCs have, but they are similarly scripted out.

The main style of the game is described with these tenets:

Moves: to do it, do it (i.e. describe what your character is doing and they are doing it)

Moves: if you do it, you do it (i.e. if you are doing a move, then roll for it, then describe what happened)

Players: your job is to play your characters as though they were real people, in whatever circumstances they find themselves – cool, competent, dangerous people, but real. (i.e. the characters aren’t heroes in the sense of traditional RPGs, they are real people, just trying to survive – so play them that way)

The MC– you have an agenda, here it is:

a. Make Apocalypse World seem real (i.e. life is tough, these aren’t super-heroes, they are civilians passing time at life; describe the weirdness of the world and accept the descriptions proferred by the players)

b. Make the player’s characters’ lives not boring (i.e. everything comes with complications, your job is to describe those and let the characters react to them)

c. Play to find out what happens (i.e. don’t pre-plan the plot, just some seeds, and play the game to see where the story goes)

Fronts

One of the things about AW that stands out is that the main rule for an MC is: You never, ever, ever, plan the outcome of anything in the game.

Following this rule makes the game more fun and more interesting because there is no predetermined ending in the mind of anyone at the table and the MC is just as surprised as the players regarding the outcomes.

But you still have to plan something, right? Yes, you do. A Front is the prepping that an MC does for the game.

I think the term, Fronts, throws people off. I like to think of Fronts as the second half of StormFront and now it makes more sense to me. In other words, the Front is the stuff that is in the Stormfront moving towards the PCs. In other other words, it is the shit that is happening around the PCs and the shit is going to hit the fan… soon. The Front spells out the options for the MC to narrate the splattering of crap as it hits the fan.

Another way to think of a Front is as a motivation. Remember that every confounding factor in the game is there to make the lives of the PCs more interesting. The Front spells out the motivations of the NPCs during the narrative. It gives the MC solid motivations for the NPCs without making their actions predetermined.

In terms of session number, Fronts do not have a specific timeline built in. The Front and all threats therein can be resolved in one session, a few sessions, several sessions, or many sessions, depending on the actions of the players.

After the very first game session, in which the MC does no prep what-so-ever, the MC has to start prepping for the game. This prep is the creation of fronts, and basically it means going down a list and choosing from specific options.

The Front as a Flowchart

The list is like a flow chart… First, choose a fundamental scarcity (that is the over-riding motivation that makes the world so dangerous for the PCs). Next, choose a threat category; if you choose threat A, then you must choose a specific thing about threat A on this other list between T and X, if you then choose item V here are the options for narrative action (i.e. the MC’s moves for that threat).

So it goes Scarcity –> Threat Category –> Impulse (the motivation of this specific threat) –> here are the available MC moves for this threat category. Choose 2 or 3 more threat categories, their related impulses, and then look at the moves available.

After you have chosen your threats, you write a one or two sentence description of the threat. Then you write down the cast of NPCs (and PCs) that are involved with that threat.

For each threat, if you like, you can create a custom move related to the threat. A custom move is just a way to allow for a special roll with special outcomes not already described in the basic/peripheral moves already described in the game.

Countdowns

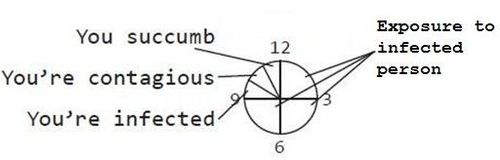

If you would like, you can also ascribe a countdown for the threat. What is a countdown? Well, this is one of those things that is hard to grasp, at least for me it was when I first read the rules. A countdown is basically a way to escalate a situation based on previous interactions or events. It’s called a countdown because it is depicted on the face of a clock (a concept almost everyone understands at a glance), but it doesn’t really denote time per se, it just denotes what stage of escalation a PC is at. The clock face is just a handy way to visualize the chain of events surrounding the issue. As things escalate, the notches on the clock get closer together and the situation becomes more dangerous and sensitive.

The countdown mechanism is, for example, a great way to track disease. Here is that as an example – note that I simplify the rolls here, only giving failure, but each roll will have a different outcome for 1-6, 7-9, and 10+:

Imagine the face of a clock…

A) At 1pm, 3pm or 6pm you can be exposed to a contagious disease. At that time you make a roll and a failure means that you have become infected. Since you have become infected, the clock automatically fast-forwards to 9pm. That doesn’t mean that it becomes 9pm in the game, it means that now the time on the clock-face that depicts the situation you are in is 9pm.

B) An infected person must make a roll at the start of every session (or you could say every morning when the PC wakes up if you want). A failure on the roll means that the disease has progressed and you are contagious. Everyone the PC comes in contact with has been exposed, and they jump on the countdown clock at part A described above (i.e. it is 1, 3, or 6pm for them).

C) You are still infected, so you are making rolls at the beginning of every session. If you fail another roll you succumb to the disease and move up to the 12 o’clock position – your PC is now taking physical harm from the sickness and may possibly die or have psychological effects (the consequences here would be described as part of the narrative).

Here is a picture of the disease countdown I just described:

Agenda

After you have chosen a few threats, then you come back to the beginning and write out some details about the Front as a whole – that is called describing the Dark Future/Agenda of the Front. The agenda isn’t a description of how the Front will be resolved, but a short 2-3 sentence description of the crap that could come to be if the Front is left to its own devices. You finish that off by naming the Front and writing out the cast of the Front.

Stakes

Then you ask some questions – and here is the important part – these are questions that you would like to know the answer to, NOT ones for which you have already determined the answer. This is called setting stakes and it is basically just writing down 2-3 questions about the fates of the NPCs (and PCs) you are most interested in.

Here is what the book says about stakes:

“Stakes should be concrete, absolute, irrevocable in their consequences. People’s lives. Maybe not necessarily their lives or deaths, at least not every time, but always materially significant changes to their lives. Resolving the outstanding question means that nothing will ever be the same for them.

They should also be things you’re genuinely interested in finding out, not in deciding. It’s the central act of discipline that MCing Apocalypse World requires: when you write a question as a stake, you’re committing to not answer it yourself. You’re committing to let the game’s fiction’s own internal logic and causality, driven by the players’ characters, answer it.”

–

Advice for new AW players

1. Before the first session, clear your mind of any preconceived notions regarding what the world looks like and why it looks that way. Also try to have no solid ideas about who each character is, despite the fact that you know what character is being played.

2. During the first session, the MC’s job is to ask you questions. Through the asking of those questions your character and the characters of others will be fleshed out and your relationships (or the possibility of those relationships) will be filled in to some extent. The world will also be fleshed out, the degree to which this happens is up to the MC and is based on the questions he/she asks – some MC’s prefer to do most of the world building during the sessions, some prefer to have a pretty fleshed out setting by the end of the first session.

3. Be ready to go with the first thing that comes to mind when you are asked a question about you character or his relationship with others.

4. The game is written so that the world is a gritty, dangerous place where people are just trying to survive. While it can be played silly, it doesn’t shine as much when played in that style. That’s not to say that there must be no humor in the game, there definitely is, but the overall setting is gritty and violent and full of sex and profanity. Be ready for that and go with the flow. If you hold back, the game won’t be exploited to its fullest – and exploitation is really what the game needs to be done right. This isn’t a bunch of polite Victorian gentlemen trying to figure out where the world went wrong, it’s a bunch of grease-monkeys, motorcycle gangs, and sleazy landlords trying to make it in the world without making too many enemies.

About Relationships

When you are first envisioning your character and the other players’ characters, think in terms of simple relationships. Then let those relationships become more fleshed out in the game. Do not decide that relationship’s details before the game is even going – let it flow naturally as the events of the game unfold.

This goes doubly for the NPCs that may be in a related biker gang or live in the same hardhold, or work in the same compound… think in terms of quick descriptions and let the narrative determine how that relationship is formed and changes. The game is about dynamic relationships, so nothing in the game will stay static for very long.

Examples of simple relationships:

NPC 1 is the best friend of PC 1

NPC 2 is the head of the brothel that PC 2 frequents

PC 3 is a hardholder and her best friend lives in the hardhold

Your MC will ask some questions to make these things come to light during the first session, and he/she may even go into detail about one or more of these relationships. Don’t be fooled – your job is to get invested during the game, not just because of some description, but because of the events that are narrated.

This may come second nature to you if you have a lot of RPG background, but it may not.

Here is an example of what I am talking about from my current AW campaign:

T-Bone is a chopper and he heads the local motorcycle gang. He is a PC. He has a relationship with an NPC that is introduced in the first session.

The only thing known in the first session is that the NPC is the lieutenant, i.e. second in command, of T-Bone’s chopper gang. The lieutenant’s name is Shithead. (This was the first word that the player blurted out when asked the name of his lieutenant, so we went with it)

We also learn that the biker gang is pretty powerful because they have control of the only refinery still in operation in this region of the US. We are then introduced to the other PCs (there are 2 of them) and an NPC related to each of them.

In the second session T-Bone finds that he can trust Shithead, who seems to be a right-hand man who functions equally well as a strong-arm and an adviser. Other NPCs are introduced as well, and things are chugging along. The main event in this session is that Shithead helps T-bone defeat an enemy of the biker gang.

In the third session, Shithead helps defuse a bad situation that would have affected the main hardhold in the town and would have eroded T-Bone’s influence. Over these two sessions (not counting session 1) T-Bone’s player has come to know and trust his relationship with Shithead.

By the time the fourth session comes around, Shithead has become envious of T-Bone’s status and power, and starts to undermine his authority. However, he still outwardly acts as a trusted adviser.

It takes T-Bone until the fifth session to figure out what is going on. At this point it is a very powerful scene and everyone is on the edge of their seats waiting to see how it will turn out. T-Bone ends up having to kill his personal assistant, adviser, trusted right-hand, and he is torn up about it and angry, he then goes on to wreak some havoc elsewhere in the town… it was a very intense and very cool session.

Much of the reason that it was so powerful was that it took 5 sessions to run that through – it wasn’t the only thing going on, but each smaller thing led to some strengthening of the undetermined (at session 1) relationship between T-Bone and Shithead. By the time the betrayal was discovered, it was awesome.

Contrast that with this: In the first session it is decided that T-Bone trusts Shithead fully and they are best buds. It is stated that Shithead has supported T-Bone in all of their exploits. In session 2 T-Bone is betrayed by Shithead. T-Bone kills shithead.

While this still might have played out as an interesting and fun session or two, it simply doesn’t have the impact that the other narrative did. Not because it was stated differently, but because it was through narrative actions in the first example that we became knowledgeable about the relationship between T-Bone and Shithead.

Just like in a good book, if you are emotionally invested in the characters, their triumph and demise will be much more powerful. In AW, it is about the narrative, so be invested in the narrative.

Why I Like It

1. The book is an interesting read and it brings in a lot of elements that I haven’t seen utilized in the more traditional games my group usually plays (or I haven’t seen them implemented well in those games). It is also an easy read, no complicated language or visualizations, just plain old descriptions of what you are to be doing in the game – and this is very specific in some instances, but surprisingly open-ended during play.

2. The author went a long way to describe the horribleness of the apocalypse in some detail, but left it open enough that the players in a particular game are able to define everything about the world. In essence, the book comes with a setting built in, but that setting has very few constraints so as to allow for maximum description and definition by the players.

3. I like that the system is simple – roll 2d6 and add your stat – no problem. Easy to understand and implement at a glance. Plus, the players (including the MC) get to make up the world and the NPCs, and the scope of everything in the game, as they go. As much as the system is scripted, the game itself is not scripted.

4. The history and advancement mechanics allow for decisive changes to be made from session to session. The structure of the game forces character interaction to the forefront, and then it rewards that type of gameplay – very classy.

5. At its heart, Apocalypse World really is a [b]story[/b] game. It is driven by the narrative of the players and that encourages buy-in and connection to the game world and the characters and NPCs, which enriches the game. It’s a vicious cycle of engagement, a perfect storm of player interaction that encourages investment and also rewards said investment.

Additional Resources

AW Main WebPage: AW Site

Lumpley Games/AW Forums: Forums

IndieRPGs Unstore: UnStore Link

RPGG AW Page: RPGG AW

RPGMP3 Actual Play AW Podcast (session 1): AW 01 RPGMP3

Walking Eye Actual Play AW Podcast (episode 1): AW 01 Walking Eye

Post Apoc Fiction: Wikipedia link to Apocalyptic fiction for inspiration

Hopefully this has given you an introduction to the game that satisfies a bit of your curiosity and perhaps inspires you to try out something new!

Publication History

Apocalypse World was first published by Lumpley Games in 2010. It was written by D. Vincent Baker and is sold on his website here: Lumpley Games AW Site.

The number of different types of PCs has been expanded since the initial publication via the release of different playsets. Most of these playsets have been awarded for specific things (e.g. buying a copy of AW at GenCon came with a special playset, purchasing the Site for Sore Eyes bundle came with a special playset, etc). These are also actively traded amongst the community, an activity that is encouraged by the author.

Any errors here are, of course, mine and mine alone; Lumpley Games and D. Vincent Baker are not responsible for any errors or omissions I have created here. Also note that this information was posted, in part, on RPG Geek as part of their Share-a-Game initiative – I wrote the post over there as well, so none of this post has been used without permission. There is a pretty good discussion going on there if you are interested in questions and clarifications for some of the things in the game that people have a hard time understanding.

Until next time, I wish you good gaming.

Now that’s a kick-ass review…

I do believe that Hx is the only stat that ever reverts back to +1/-1. All other stats cap at +3.

You are correct – sorry I was unclear about the highlighting of stats and advancement.

You are right that Hx is the only one that goes to -1. The other stats go up to 3 only. You fill in improvement circles when you use highlighted stats (which are chosen at the beginning of each session). When the 5th improvement circle is is filled in, you start over at zero for the imp circles and then improve a stat. This is all on page 180.

Thanks for catching that.

Good overview there Sam.

Thank you for writing this review/breakdown of Apocalypse World. I recently picked up the book and pdf in hopes of running it, and your write-up is a huge help in better understanding the game along with its potential.

I started running a Deadlands Hell On Earth campaign not too long ago that I’m contemplating carrying my players over from. Their play-style has evolved to more of a narrative driven game. I’d probably just have them adapt their characters into appropriate playbooks and have them start as if the other campaign never occurred.