Wizards of the Coast recently released Waterdeep: Dungeon of the Mad Mage, which features Undermountain, one of the most iconic locations in the Forgotten Realms setting. This location has a long history, seeing first publication in 1991 – just a couple of years after the publication of the 2nd edition D&D Player’s Handbook. It was expanded upon several times during the 2e years and has enjoyed product releases in every subsequent edition. In case you didn’t know this already, Undermountain is a MEGADUNGEON!!!! While there are certainly large dungeons in 5e adventure modules, 5th edition hasn’t previously focused on megadungeon play so I thought it might be helpful to provide you with some tips and advice for running your group through a megadungeon. This is also advice for players who are going to be run through a megadungeon – the information here can help you play a great dungeon campaign!

all rights reserved

The main difference between a megadungeon campaign and any other type of campaign is the environment in which the party will spend the majority of their time. The megadungeon environment is different from others, and so with that in mind, let’s talk about how the game play is different when the party is in that environment.

Resource Management As Game

There are several things that differentiate megadungeons from smaller dungeons. One of the most important, of course, is the size of the dungeon. megadungeons are enormous, often multi-layered, locations that seem to go on-and-on-and-on. They often have multiple entrances and exits so that the party can find a variety of ways to get in and out of the place. Because of the vastness of the location, a campaign focused on the megadungeon will see the party spending the majority of their time inside. There may be forays back to town to store loot, replenish supplies, and rest up in a comfortable bed, but the meat of the adventure is within the walls of the dungeon.

The frequency with which a group gets to visit town and replenish supplies becomes an important part of the experience. The party will have to take care to have the right amount of consumables to get them far enough along that they feel they’ve made good progress and accomplished something before having to venture back out of the dungeon. As such, the megadungeon becomes a resource management game.

Which resources have to be managed?

Torches: This may not seem like a big deal in 5th edition D&D because the Light spell is a cantrip. Most people, therefore, might assume that if they have a Bard, Cleric, Sorcerer, or Wizard, they will have no problem with light in a megadungeon. However, it is trivially easy to get rid of magical light. Here are 4 cases where the Light spell isn’t the answer:

1) Some creatures have the ability to create anti-magic effects (e.g. Beholders, Astral Dreadnoughts).

2) Darkness, the 2nd level evocation, can disrupt Light if it was cast as a 2nd level spell or lower. And trust me, your spellcasters are NOT going to want to spend a 3rd level spell slot on Light! Multiple creatures can cast or have an aura of Darkness, including Babau, Black Abishai, Blue Abishai, Darkmantles, Dhergoloths, Draegloths, Drider, Drow (all types), Glabrezu, Gynosphinx, Hydroloths, Merrenoloths, Mezzoloths, Morkoths, Nycaloths, Oinoloths, Oni, Shadar-Kai Gloom Weavers, Ultraloths, Yagnoloths, Yuan-ti Anathema, and any spellcasting NPC your DM chooses.

3) The DM (or the designer of a published megadungeon) can place an effect causing an antimagic field, aura of magical darkness, or dispel magic area anywhere in the dungeon. Whether it is triggered by a trap, is a permanent affect on a given room, or exists for some other reason, it is trivially easy for this challenge to affect the party.

4) If the spellcaster gets killed the party has lost the ability to cast that spell for the time being. And I haven’t even mentioned all of the creatures that could cast dispel magic on a Light object. Have I convinced you that torches are your friend yet?

Food: One day of rations costs 5 silver pieces and weighs 2 pounds. How long does the party think it is going to be in the dungeon? Does food ever spoil? Even with magical intervention, this is something that the party should be thinking about. Managing enough food for all to survive is a valuable skill.

Rest: This one is important because it is related to healing. In 5th edition D&D the party will have to manage 2 types of rest periods – the short rest and the long rest. A short rest is a minimum of 1 hour and the PCs can use hit dice (HD) at the end of the rest to heal. Notice I italicized at the end because if the rest gets interrupted the party doesn’t get to heal. Where are they going to rest? Is it safe? What are the chances of the rest being interrupted by a wandering monster? These are all questions that matter to a group that is 7 levels deep in a megadungeon and doesn’t have a quick way of exiting the hellish place.

A long rest is a minimum of 8 hours and can only occur once in every 24 hour period. All of the same questions asked above about the short rest are also important to the long rest, maybe even more so. Just as in a short rest, the healing benefits of the rest do not take place until the end of the rest. The long rest allows the PCs to heal all HP and regain half of their total HD. That last part is important because it means HD are a resource that must be managed as well. If an 8th level PC has a long adventuring day and spends all 8 HD, they only regain 4 of those for use the next day. If a party is going to be adventuring in a dungeon for days on end it becomes important to manage rest time, HD resupply, and the safety of locations.

Consumable Supplies: Other than food. These are things like bolts, arrows, healing kits, flasks of oil, torches, water, iron spikes, and other similar items. Even groups that don’t normally keep track of expended arrows or how many iron spikes they have used should recognize that this might become important after an extended period of time in the megadungeon. Don’t be careless! Should you track this down to the most minute details? Only if that is fun for your group, of course. However, you should also recognize that the dungeon itself might have an area that causes your food to spoil, your pack containing tinder and torches to fall down a bottomless crevasse, or your quiver of arrows to fall into the underground river and get swept away by the fast moving current. Those situations would then require some creative sharing of resources to get the party through until the next trip back to town.

Time: All of this adds up to proper management of the most important resource of all… time. If your D&D party is used to wilderness adventures where they frequently encounter towns or villages of civilized folks they will likely not be concerned with time. If your party is used to the proverbial 5-minute-workday, they may not be used to thinking of time as a resource to be managed in-game. This is a difficult concept to understand for some groups, but time in the dungeon really is something to be managed and planned. They should try to determine how long they will be in the dungeon between resupply runs, and this is probably something the DM should talk to the players about before the first session of the campaign, especially if the players have not played in a megadungeon campaign previously.

Factions in the Megadungeon

Every good megadungeon has a living ecosystem – and here I am not talking just about creature types making sense in the dungeon. I’m talking about the factions, opposing creature groups, allied creature groups, and wandering monsters that make sense. I’m also talking about different types of biological environments inside the dungeon complex itself. Most megadungeons offer a variety of regions (e.g. an underground forest, a tomb, an ancient mine, a natural cavern system, a flooded area, or an abandoned dwarven palace) in the megadungeon. These aren’t always on different levels and they often have groups of creatures inhabiting them who are at odds with each other. These are the different factions in the dungeon and they all should interact with each other in different ways, and they should interact with the PCs in different ways as well.

These factions allow you to interject some politics and negotiation into your megadungeon experience. A megadungeon isn’t all just rush in, kill the beasts, and run out with the loot! It also includes negotiating a peace treaty between the lizardman tribe and the svirfneblin community. Or negotiating new territorial boundaries between the two warring kobold warrens. Or helping the rogue band of goblins find their way through the mushroom commune without getting accosted. There can be power struggles between any groups of creatures found in a megadungeon, whether they are human-based or not doesn’t matter – most creatures will do what they can to survive and their chieftains will attempt to better the situation of their whole group. This is where the party comes into play and helps or hinders one group or another. The benefits of this can be amazing, and much better than just slaughtering every creature they come in contact with.

So how do you prep for such a thing?

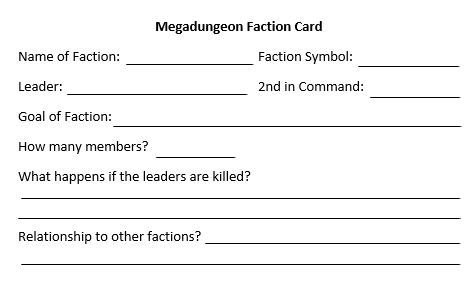

I use 3×5 cards to keep track of the factions in my megadungeon, but you can use whichever type of note-taking device you prefer. I write down very specific information about each faction on the card. Here is a sample blank faction card:

This set of cards allows me to have a quick shot of what each faction wants (their goal), how big each one is (# members), and how they mark their territory (symbol) at a glance. I can write notes on them during the game to remind myself of the deals made or disposition of the faction toward the PC group. This makes it easy to run several factions and create interesting interactions for the party to witness or participate in. I also color code the card at the top with a crayon or colored pencil mark and then use that same color to denote the territorial boundaries for that faction on my DM map.

Wandering Monsters

Along with the factions of permanent residents in the megadungeon, there are often wandering monsters roaming the halls. As a DM it is important to note the types of creatures found in each region and the frequency with which they might be encountered. Sometimes a monster encounter isn’t random… if the group is making a lot of noise hammering an iron spike into the wall to make sure that portcullis doesn’t close behind them, it is likely that a nearby creature will come out to see what is disturbing its nap! That means that you need to be familiar with the inhabitants of the region the group is exploring so that you can respond to the activities of the PCs with appropriate creature behavior. In other words, the rooms of the megadungeon aren’t full of monsters just waiting there for the party to come in and attack them. No monsters in boxes!! If a creature hears a battle down the hall, they are likely to either run away to save their own skins, or come and join the fray. They are NOT likely to just sit in their room wondering when the party is going to come and visit. When you prep for each session, try to refresh your memory of the creatures in the region and track their movements in your notes. This is easier than it sounds – make it a habit and it will become no big deal.

You should also consider how the dungeon changes over time. If the party cleared out a cave system of all the kobolds on the second level of the dungeon two months ago, is that region still empty? What has moved in and taken over that space? Did the party kill the Gelatinous Cube that roams level 6? Who is cleaning the dungeon now? Did the group kill the two Otyughs in the refuse pit on level 4? Now where is the troglodyte clan supposed to dump their garbage? Did the party leave for two weeks to heal up and take care of business in town? How have the relationships between factions changed since the party left? The dungeon is not a static place and you need to have a plan for restocking and repopulating the cleared out regions if the party stays gone long enough.

Encumbrance

Are you going to use encumbrance rules? Does it matter if the party is trying to carry out 50,000 coins, 12 heavy tapestries, 4 urns, 7 wooden chests, and a large bronze statue? You don’t have to follow a strict set of encumbrance rules, but you should decide what the party can realistically carry and talk to your players about it. Sure, you may not want to track how many arrows the ranger has used, or how many fist-sized rubies the halfling pocketed, but there is a ‘common sense’ limit on what can be carried and you should inform your players about how you will rule on it if this becomes a question during the campaign. You may just decide not to worry about it and not count encumbrance at all, and that is a fine way to play if your group agrees, but recognize that decision may have unforeseen consequences when running a multi-level megadungeon.

Followers and Hirelings

Are you going to allow your party to bring followers into the dungeon? Will they purchase the services of hirelings? You can find information about both of these types of underlings on pages 92-94 of the Dungeon Master’s Guide. This is definitely something you should think about and discuss with your players before you start your campaign. Other than followers and hirelings, you could use a third class of helper NPC – the torchbearer. This person acts only as a light source bearer and treasure carrier for the group. Allowing a few torchbearer NPCs to be hired by the group for, say, 1 sp per day, might help solve the problem of encumbrance tracking and torch use.

Mapping

Are you going to draw a map for your players? Make them draw the map based on your descriptions? Use a flip-mat, vinyl map, dungeon tiles, 3D terrain, or other mapping accessory? This comes down to preference, for sure, and each of the choices has benefits and drawbacks.

Having one of the players act as a scribe and draw the map based on your descriptions can be interesting and fun, and lead the players themselves to find interesting structural areas in the map (“That is a weird gap – I’ll bet there is a secret room there!”). Or it can be tedious and cause the game to slow to a crawl as the player tries to perfectly draw the oddly shaped cavern or the multi-dimensional tesseract trap they just entered. Are you going to correct the player if their map is incorrect? How many times will you repeat your description?

Having the party find a map or partial map in-game is a good way to allow for the players to access a map without giving them a 100% accurate DM’s map of the region. You will have to prep this map before running the game, so make sure you built time into your schedule for this.

If you use dungeon tiles or a flip-mat you are drawing on yourself, do you pre-draw the region to save time during the game? Do you drawn one room at a time? Do you draw it out but somehow cover the unexplored areas? Do you build it with expertly painted 3D terrain? That is gorgeous, but how do you keep the party from seeing the whole region you built? All of these are questions you should consider while you are prepping your campaign. And remember, it’s okay to try something and decide to change if you decide you don’t like it!

Tips & Advice

To finish this article off I’ll give you a quick set of tips for running a megadungeon.

- Familiarize yourself with the mechanics of encumbrance, locked doors, secret doors (finding them), traps (triggering, detection, and resetting them), surprise rounds and ambushes, stealth, and vision/light. These are all things that are common in megadungeons and you should know how you will adjudicate them.

- Know the goals of the factions in the dungeon and where the territorial lines are drawn. Having faction notes ready while you are running the game will save time and stress.

- Learn to describe the state of stone walls, floors, and ceilings in a way that provides clues to the party. Does that wall look old and crumbly? Maybe it is a false wall they should investigate, or maybe it will fall in on them!

- Let the history of the dungeon be discoverable. This is something I didn’t touch on earlier, but megadungeons often have a long history of in-game faction wars, NPC rivalries, and calamitous events. As the party moves through the dungeon they should come across artifacts that give clues about the history of the place. Scenes depicted on tapestries, tile mosaics, bas reliefs, words scrawled on walls, symbols etched onto columns, desecrated altars that have been reclaimed… all of those are clues to the history of a place because they can tell a story.

- You should also provide clues to the party with respect to faction territorial boundaries and dangerous areas. Faction symbols scrawled on passageways or a symbol scraped onto the base of a statue is enough to clue the party in to who lives there.

- Use all 5 senses when describing the environment. Not just the look of the walls, floors, ceilings, but the smell of the place. Does the air have a taste? Does the party hear distant sounds?

- Be familiar enough with the current area being explored that you have an idea if another set of creatures will show up when noise happens.

- Set your player’s expectations!

The Importance of Goals

Even if you only have only a single starting hook designed to get the party to travel to the entrance of the megadungeon, there should be more to discover and keep them going as they explore deeper and deeper. One of the things that makes a megadungeon campaign possible is that it is more than just a bunch of rooms filled up with creatures to kill and loot to steal. The party should be paying attention to what is happening to all aspects of the dungeon – factions, creatures, territories, traps, symbols, images, and other pieces of the environment that indicate this dungeon has a history. In other words, the dungeon isn’t dead, it is a living breathing ecosystem of creatures and situations which can lead to many different challenges and goals. As the group is traveling through the dungeon they should come face to face with multiple opportunities to flesh out the ‘story’ of the dungeon.

And by that I mean the story of the dungeon as it is now, not the backstory or history of the dungeon (though that can become important, too). Who lives in the dungeon? What do they need? Can the party bargain with them, assist them, or otherwise interact with them to change the conditions in the dungeon? Will this lead to more challenges and goals? Will this get the party one step closer to completing their main mission? What smaller tasks might present themselves to give the party focus? In this way a megadungeon isn’t so very different from any other type of adventure – smaller goals need to be accomplished in order to build up to finishing larger tasks, completing bigger goals, and affecting the world around them. As they satisfy more goals they gain experience, meet NPCs, learn about the setting, and increase their competency, which they then use to complete even more goals.

Running a megadungeon can be a rewarding, fun, exciting campaign! I hope this article helps you run your best dungeon! We recently recorded an episode of the Tome Show that discusses this very topic – have a listen if you want to hear what Rabbit Stoddard, Dan Dillon, Neal Powell, and Jeff Greiner have to say about the topic!

Thanks for reading and, as always…

Until Next Time, I wish you good gaming!

Having read another of your epic posts. I feel you have a lot in your chest to get off.

Mega-Dungeon.

Never ran a successful dungeon crawl any farther than a few sessions, where I felt the players had had enough so I called it a day and took the story outside.

Anyway.

I see everything you say here could also work for a City based game.

Factions and societies, secret or know. Waring sides (gangs) and so on. How food is brought in and how it is traded.

So if I deal with a City just like a mega-dungeon I feel like I can’t go wrong.

Thanks again for a great article.

Sy

Thanks Symatt! And you, you are entirely correct! This advice basically applies to any setting or region with a little bit of tweaking! Cheers!